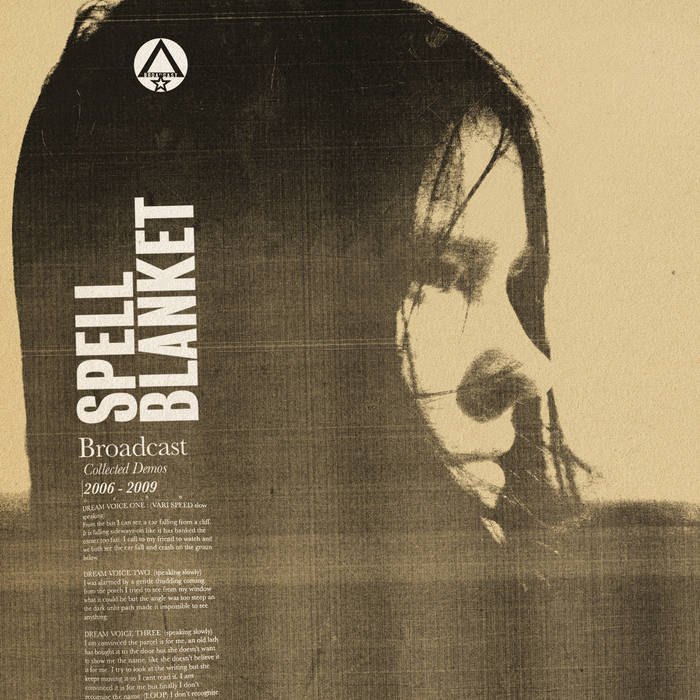

Albums don’t get much more bittersweet than Spell Blanket, Broadcast’s recently released collection of demos that were recorded by late singer Trish Keenan from 2006–2009. For long-time obsessive fans like myself, there is joy in hearing Keenan’s voice again on unheard material and once again being inspired by her creativity. There is also an unmistakable sadness in the experience, hearing all these ideas and knowing how much great future music was taken from us when she passed. The more exciting and mesmerizing a song on Spell Blanket is, the more it hurts that it represents a fascinating path she was never able to fully explore.

Right away, the second song, “March of the Fleas,” stands out as a new direction for Broadcast, as Keenan’s haunting voice gets buried under cascades of heavy noise, like she’s being sucked into another dimension and is taking you with her. Then the song ends in two minutes and the reality sets in that there can never be a full album of songs like it, and this is it. Spell Blanket sprawls over 36 tracks — some seem nearly complete, others are more like snippets of possible directions — and most of them spark this sort of feeling. Between the quantity of material, the typical depth of Keenan’s ideas, and the emotional baggage involved in getting to hear any of this at all, it’s very difficult to process despite the inviting sounds.

James Cargill, Keenan’s bandmate/partner, had the unenviable task of assembling these demos, and he’s done it in a way that makes it feel like an actual artistic statement instead of a pile of tapes. The inherent minimalism in the demos suits Broadcast well: what makes their music brilliant and enduring is how he and Keenan could conjure complex feelings and ideas from very simple elements. Psychedelic music is often mistakenly thought to need a huge collection of instruments and effortful weirdness; Keenan could sing a bunch of one-syllable words over one synthesizer or some light strumming and transport listeners to different worlds.

“Follow the Light” was released as the first single off Spell Blanket, and it’s a quintessential Broadcast song. Keenan creates magic out of basically nothing: she sings some repetitive lyrics like “follow the light/look into the light” over a quiet synth part, yet the result is practically mind-blowing because so much is unsaid and left open to the listener’s interpretation. Broadcast’s music is always generous in this way. There is never any pretension, or an attempt to seem cool; the band wanted listeners to find new ideas in the music and explore, and Keenan was the perfect relatable voice to nudge them along.

That song also shows Keenan’s warmth as a presence, and a lot of what I find compelling in Broadcast’s music is the merging of psychedelia with humanity. That shines through in these sparser demos, which put the spotlight even more on Keenan’s natural gift for melody and her innate likability. “A Little Light” is a brief sing-songy burst of unadulterated uplift reminiscent of “Come On Let’s Go,” where Keenan tells someone to focus on the positives in a way that comes off as genuine and not cliche. Another happy song is “Petal Alphabet,” but its lyrics are more of an abstraction built around evocative phrases, in line with the work Broadcast was doing on later albums like Tender Buttons. Keenan shows vulnerability on the affecting “I Want to be Fine,” alternating spoken word mumbling and her delicate singing voice to sound fragile and even desperate. In some ways, the album in this form feels like a natural progression Broadcast could have made because of how much it emphasizes the human element that separated them from so many other psychedelic bands.

With no way of knowing what these demos would have eventually turned into, it’s better to accept what Spell Blanket is, which is a final testament to Keenan’s creativity, charm, and constant pursuit of new sounds and ideas. Even in its somewhat unpolished form, everything that made Broadcast a special band is present here, and it also includes some new ideas that show different lanes they could have eventually gone down. There’s something that sparks the imagination in all 36 of these songs, no matter how short they are, and some of the high points even benefit from the stripped-down non-performative demo feel. Unfortunately, the quality of Spell Blanket is also a kind of tragedy, as it clearly shows just how much Keenan had left to give.