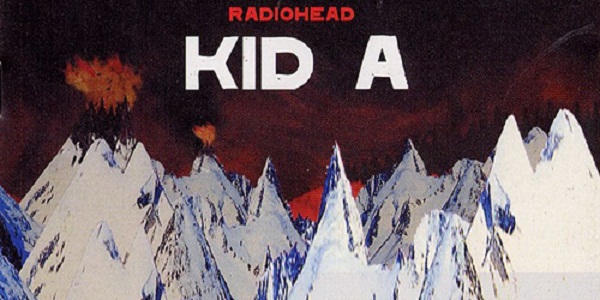

I can’t speak for all Radiohead fans, but the music I initially loved by the band was showcased on 90s albums The Bends and OK Computer, a complex yet accessible guitar-based alternative rock sound. The story of 2000’s Kid A is well-known by now — burdened by the expectations of following up OK Computer and looking to evolve as a band, the group reinvented themselves, creating an atmospheric, electronic-based album that has little in the way of radio-friendly singles or mainstream appeal. At least that was the idea, but Kid A became one of the oddest chart-topping albums in music history.

Personally, I hated it. I began getting into Radiohead chronologically, and after loving The Bends and especially OK Computer, Kid A felt like a slap in the face. I felt like the band had betrayed me and that Kid A was just a calculated attempt to piss off my adolescent self who wanted more big guitar songs about being depressed. Even today, it seems like there is a divide among Radiohead fans between those who love their 90s guitar albums and those who prefer their more complex,challenging output from the 2000s.

It took a couple years before I decided to revisit the album, and since then I guess my tastes had evolved somewhat. I suddenly had an urge to listen to Kid A. This time it clicked and made sense to me. (It was strikingly similar to this Onion article where Bill Gates finally gets into the album after several months.)

Nonetheless, I still feel slightly ambivalent about it, because Kid A received such a massive amount of slobbering acclaim at the end of 2009, when it topped most publications’ end of decade lists. It bothers me because I think Kid A has become more about a narrative surrounding the album than its actual music — it’s about the internet age, or the changing landscape of music, or the growing influence of electronica, or whatever. I’ve never felt comfortable shoving an album into a narrative box the way everyone seems to do with Kid A.

Instead, I would rather think about Kid A as it pertains to Radiohead themselves, which is where I think its true greatness lies. For a band in their position, it was an incredibly risky album. These days, it’s hard to imagine another band in that position pulling off such a radical shift when they could easily succeed by doing what they’ve been doing. Kid A is very unique in this regard: it required a band like Radiohead having confidence in themselves that they could make it, but also confidence that their rabid, intelligent fanbase would go along with them on the journey.

Kid A didn’t exactly come out of the ether though — listening to OK Computer, I can sometimes hear the beginnings of this phase of the band (especially on tracks like “Fitter Happier” and “No Surprises”) and the album has clear influences in electronica, jazz, and krautrock. Plus it still sounds like Radiohead, mostly because of Thom Yorke’s signature voice, which is always recognizable even when he’s singing lyrics that are often incomprehensible.

Kid A boasts what is probably the best opening song of the decade with “Everything In Its Right Place.” It’s an incredible tone-setter, its lack of guitar and ominous electric piano part instantly indicating that this is album is going to be different. Overall, what sometimes gets forgotten about this album is that it has incredible pacing, the perfect opener giving way to the abstract title track and then the throbbing bass groove of “The National Anthem” (which I wish really was the national anthem).

After Radiohead comes out of the chutes with the most distant, abstract music of their careers, the back-half of Kid A is more accessible. Guitar-driven “Optimistic” is the closest Radiohead comes to recalling their 90s sound, but it has more experimentation than some give it credit for, especially with the jungle-style rhythms. It’s my favorite song on the album, as a testament to my perpetual uncoolness. “Idioteque” is the album’s beat-heavy centerpiece, and it bleeds into “Morning Bell” which is another more accessible song that seems to foreshadow the band’s work on In Rainbows.

Radiohead forsaking their rock roots for Kid A looks especially prescient now after a decade where The Bends style rock fell out of favor with most people. Radiohead had already gained a reputation for making amazing music, but Kid A is where they became known as game-changers and trendsetters, fully establishing themselves as a band that would always play by their own rules.